A Southern Fire-Eater Witnesses John Brown's Hanging

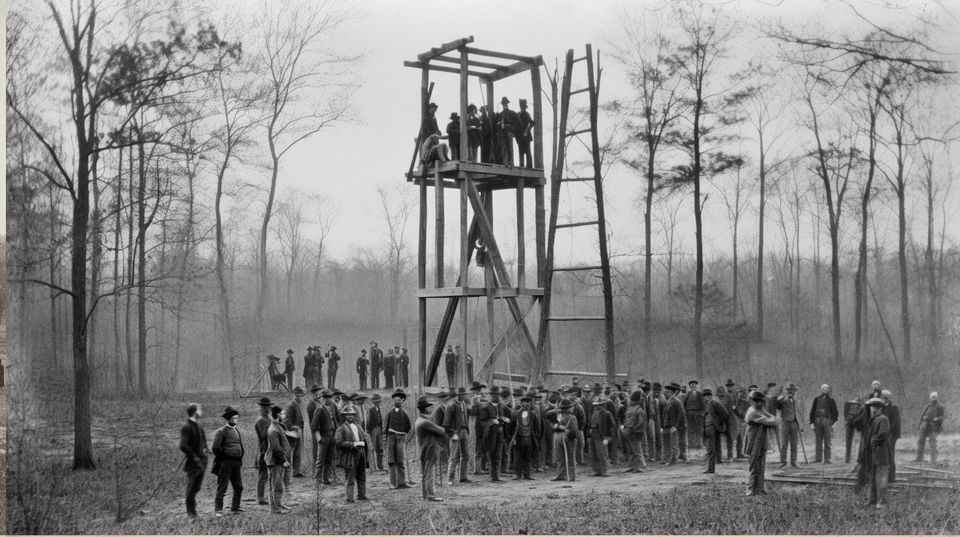

Welcome to Antebellum Etc., where I'll explore various facets of the culture wars that led to the Civil War, and in some cases the culture wars that followed it. Most posts – or emails, if you're getting them in your inbox – will coincide with videos posted to my YouTube channel, and therefore contain the embedded video followed by additional context, commentary, and links to sources. First up: Excerpts from the diary entries of Virginia "fire-eater" Edmund Ruffin, who traveled to Harpers Ferry – the "seat of war," as he called it – to witness the 1859 execution of the violent abolitionist John Brown in nearby Charles Town.

It's interesting and somewhat counterintuitive to contrast Ruffin's reaction to and particpation in the aftermath of Brown's failed raid with Ruffin's 1862 recollection of the "state of insanity of a community ... in lower Va. & N.Ca. following & caused by the insurrection of slaves & their massacre of whites in Southampton County" in 1831 – the Nat Turner revolt.

"There was full proof that the knowledge of the design was confined to three persons only, until within a few hours of the beginning of the massacre, & that it could not have been previously divulged elsewhere, or to others," Ruffin wrote. "Yet terror & fear so affected most persons as to produce a condition of extended & very general community-insanity. ... Many slaves, who certainly had never heard of the insurrection until after its complete suppression – & some 100 miles & more from the scene – were charged with participation, & tried & condemned to death, on testimony of facts, or from infamous witnesses, which at any sober time would not have been deemed sufficient to convict a dog suspected of killing a sheep."

Ruffin found the case against one falsely convicted slave so egregious that he "exerted myself to get up a petition to the governor (which I wrote) for the pardon of this convict. There was scarcely any person to whom I applied who did not believe the man innocent, but who still did not refuse to meddle with the matter so far as to sign the petition – to which I could obtain but 11 signatures besides my own." Ruffin nevertheless went to Richmond to deliver the petition to Governor John Floyd, who "did not dare, or deem it politic, to grant the petition, or to pardon in any such case." And Ruffin "did not escape much odium ... & even intimations were uttered that I ought to be punished by personal violence. Some who thus joined in condemning me had previously confessed to me their belief in the entire innocence of the convict."

Less than four years after Brown's hanging, Harpers Ferry and Charles Town, which were part of Virginia at the time, became part of the newly formed Union state of West Virginia – a contigency foreshadowed by Ruffin's observation that the "people hereabout are much more unionists than in lower Virginia" and "generally disapproved" his "disunion sentiments." (Brown's pike – one of many he had brought to Virginia with the intention of arming slaves – would keep attracting attention as Ruffin traveled with it to Washington and Richmond, and he asked the superintendent of the Harpers Ferry arsenal to send more, which he arranged to have labeled and distributed to the governor of each slave state. The fact that 1859 was anything but a "sober time" suited Ruffin's secessionist aims perfectly.)

Virginia itself, the 1831 overreaction to the Turner revolt notwithstanding, was too moderate for Ruffin. He gravitated toward the more radical (if wishy-washy) mood of South Carolina, corresponding with James Henry Hammond and Robert Barnwell Rhett, the latter of whom had advocated secession as early as the 1820s, and whose newspaper the Charleston Mercury provided an occasional outlet for Ruffin's screeds. On election day, Nov. 6, 1860, Ruffin voted for John C. Breckenridge – one of the three alternatives to Abraham Lincoln, whose divided opposition assured the victory Ruffin and other fire-eaters hoped would force Southerners "to choose between secession & submission to abolition domination." Ruffin then immediately left for South Carolina, "where I hope that even my feeble aid may be worth something to forward the secession of the state & consequently of the whole South."

He immediately felt more at home than he had all his life in Virginia, where his innovations in agriculture were too often underappreciated, though they had done much to rejeuvenate the exhausted soil of the Tidewater South, where his petitions generally went unsigned, and where the politics so frustrated him that he resigned his one term in the state senate a year before it ended. Ruffin wrote his sons from South Carolina that the "time I have been here has been the happiest of my life. ... The public events are as gratifying to me as they are glorious & momentous. And there has been much to gratify my individual & selfish feelings." His mood constrasted markedly with that expressed in his diary the day before learning of the John Brown raid on Harpers Ferry, when he complained of having "latterly felt more the want of occupation than since giving up my business" and having "no object whatever to strive for."

He made a few return trips to Virginia, but with the formation in early 1861 of the Confederate States of America – initially without Virginia – he decided again to decamp to South Carolina before Lincoln's inauguration to "avoid being, as a Virginian, under his government even for an hour." In recognition of Ruffin's "feeble aid" to the secessionist cause, the Palmetto Guards, whose Iron Brigade he had joined, gave him the honor of firing the first shot at Fort Sumter on April 12, and he wrote that he was "highly gratified by the compliment, & delighted to perform the service – which I did."

The following week, a grandson was born and named Edmund Sumter Ruffin, and the same week Ruffin learned that Virginia had finally seceded, so he returned home. Four years later, consistent with his pre-war refusal to live under Lincoln's government – though by then Andrew Johnson was president – Ruffin wrote a final diary entry declaring "my unmitigated hatred to Yankee rule – to all political, social & business connections with Yankees – & to the Yankee race," and, with the aid of a forked stick, shot himself with his rifle.

"His children found his lifeless body still sitting upright, defiant and unyielding even in death," writes historian Eric H. Walther in The Fire-Eaters, which along with Ruffin's diary is the source for this post. Ruffin also figures in David S. Heidler's Pulling the Temple Down: The Fire-Eaters and the Destruction of the Union.

(This video uses public domain images and AI visualizations.)