Extremists Take Over in the Wake of the John Brown Raid

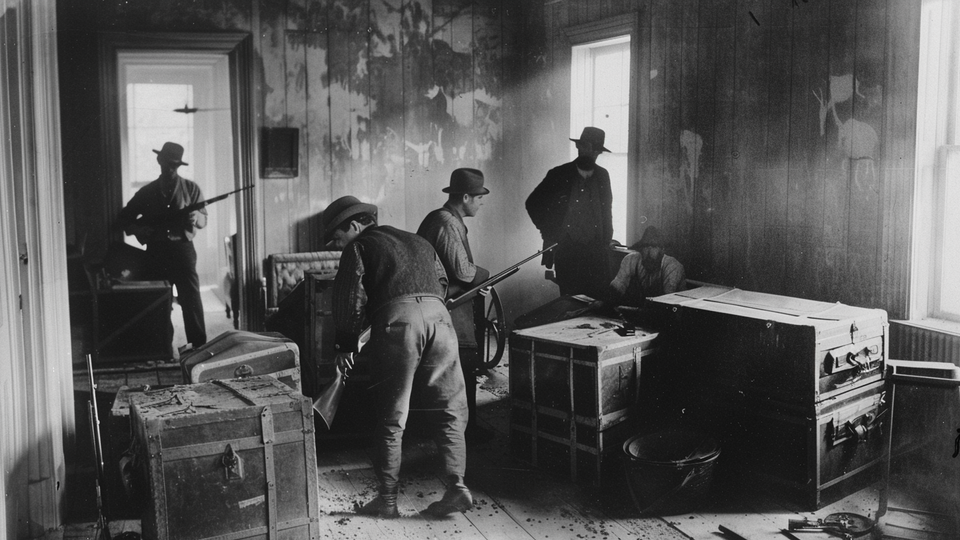

This week's video introduces viewers to the "Secret Six," a group of Northern elites whose clandestine support of John Brown's attack on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry spread panic across Virginia and beyond, giving Southern fire-eaters the opportunity they had been waiting for.

C. Vann Woodward's essay "John Brown's Private Army," which is included in his collection The Burden of Southern History, shows how the Harpers Ferry raid unleashed the extremists on both sides of the Mason-Dixon line:

The crisis of Harpers Ferry was a crisis of means, not of ends. John Brown did not raise the question of whether slavery should be abolished or tolerated. That question had been raised in scores of ways and debated for a generation. Millions held strong convictions on the subject. Upon abolition, as an end, there was no difference between John Brown and the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. But as to the means of attaining abolition, there was as much difference between them, so far as the record goes, as there is between the [20th-century] British Labour Party and the government of Soviet Russia on the means of abolishing capitalism. The Anti-Slavery Society was solemnly committed to the position of nonviolent means. In the very petition that Lewis Tappan, secretary of the society, addressed to [Virginia] Governor [Henry] Wise in behalf of Brown he repeated the rubric about “the use of all carnal weapons for deliverance from bondage.” But in their rapture over Brown as martyr and saint the abolitionists lost sight of their differences with him over the point of means and ended by totally compromising their creed of nonviolence.

But what of those who clung to the democratic principle that differences should be settled by ballots and that the will of the majority should prevail? Phillips pointed out: “In God’s world there are no majorities, no minorities; one, on God’s side, is a majority.” And [Henry David] Thoreau asked, “When were the good and the brave ever ina majority?” So much for majority rule. What of the issue of treason? The Reverend Fales H. Newhall of Roxbury declared that the word “treason” had been “made holy in the American language”; and the Reverend Edwin M. Wheelock of Boston blessed “the sacred, and the radiant ‘treason’ of John Brown.” No aversion to bloodshed seemed to impede the spread of the Brown cult. William Lloyd Garrison thought that “every slaveholder has forfeited his right to live” if he impeded emancipation. The Reverend Theodore Parker predicted a slave insurrection in which “The Fire of Vengeance” would run “from man to man, from town to town” through the South. “What shall put it out?” he asked. “The White Man’s blood.” The Reverend Mr. Wheelock thought Brown’s “mission was to inaugurate slave insurrection as the divine weapon of the antislavery cause.” He asked: “Do we shrink from the bloodshed that would follow?” and answered, “No such wrong [as slavery] was ever cleansed by rose-water.” Rather than see slavery continued the Reverend George B. Cheever of New York declared: “It were infinitely better that three hundred thousand slaveholders were abolished, struck out of existence.” In these pronouncements the doctrine that the end justifies the means had arrived pretty close to justifying the liquidation of an enemy class.

The reactions of the extremists have been stressed in part because it was the extremist view that eventually prevailed in the apotheosis of John Brown and, in part, because by this stage of the crisis each section tended to judge the other by the excesses of a few. “Republicans were all John Browns to the Southerners,” as Professor Dwight L. Dumond has observed, “and slaveholders were all Simon Legrees to the Northerners.” As a matter of fact Northern conservatives and unionists staged huge anti-Brown. demonstrations that equaled or outdid those staged by the Brown partisans. Nathan Appleton wrote a Virginian: “I have never in my long life seen a fuller or more enthusiastic demonstration” than the anti-Brown meeting in Faneuil Hall in Boston. The Republican press described a similar meeting in New York as “the largest and most enthusiastic” ever held in that city. Northern politicians of high rank, including Lincoln, Douglas, Seward, Edward Everett, and Henry Wilson, spoke out against John Brown and his methods. The Republican party registered its official position by a plank in the 1860 platform denouncing the Harpers Ferry raid. Lincoln approved of Brown's execution, “even though he agreed with us in thinking slavery wrong.” Agreement on ends did not mean agreement on means. “That cannot excuse violence, bloodshed, and treason,” said Lincoln.

Republican papers of the Western states as well as of the East took pains to dissociate themselves from Harpers Ferry, and several denounced the raid roundly. At first conservative Southern papers, for example the Arkansas State Gazette, rejoiced that “the leading papers, and men, among the Black Republicans, are open ... in their condemnation of the course of Brown.” As the canonization of Brown advanced, however, the Republican papers gradually began to draw a distinction between their condemnation of Brown's raid and their high regard for the man himself—his courage, his integrity, and his noble motives. They also tended to find, in the wrongs Brown and his men had suffered at the hands of slaveholders in Kansas, much justification for his attack upon Virginia. From that it was an easy step to pronounce the raid a just retribution for the South’s violence in Kansas. There was enough ambiguity about Republican disavowal of Brown to leave doubts in many minds. If Lincoln deplored Brown, Lincoln’s partner Billy Herndon worshipped Brown. If there was one editor who condemned the raid, there were a half dozen who admired its leader. To Southerners the distinction was elusive or entirely unimportant.

Northern businessmen were foremost in deprecating Harpers Ferry and reassuring the South. Some of them linked their denunciation of Brown with a defense of slavery, however, so that in the logic that usually prevails in time of crisis all critics of Brown risked being smeared with the charge of defending slavery. Radicals called them mossbacks, doughfaces, appeasers, and sought to jeer them out of countenance. “If they cannot be converted, [they] may yet be scared,” was Parker’s doctrine.

Among the Brown partisans not one has been found but who believed that Harpers Ferry had resulted in great gain for the extremist cause. So profoundly were they convinced of this that they worried little over the conservative dissent. “How vast the change in men’s hearts!” exclaimed [Wendell] Phillips. “Insurrection was a harsh, horrid word to millions a month ago.” Now it was “the lesson of the hour.” Garrison rejoiced that thousands who could not listen to his gentlest rebuke ten years before “now easily swallow John Brown whole, and his rifle in the bargain.” “They all called him crazy then,” wrote Thoreau; “Who calls him crazy now?” To the poet it seemed that “the North is suddenly all Transcendentalist.” On the day John Brown was hanged church bells were tolled in commemoration in New England towns, out along the Mohawk Valley, in Cleveland and the Western Reserve, in Chicago and northern Illinois. In Albany one hundred rounds were fired from a cannon. Writing to his daughter the following day, Joshua Giddings of Ohio said, “I find the hatred of slavery greatly intensified by the fate of Brown and men are ready to march to Virginia and dispose of her despotism at once.” It was not long before they were marching to Virginia, and marching to the tune of “John Brown’s Body.”

The Harpers Ferry crisis on the other side of the Potomac was a faithful reflection of the crisis in the North, and can therefore be quickly sketched. It is the reflection, with the image reversed in the mirror, that antagonistic powers present to each other in a war crisis. To the South John Brown also appeared as a true symbol of Northern purpose, but instead of the “angel of light” Thoreau pictured, the South saw an angel of destruction. The South did not seriously question Brown’s sanity either, for he seemed only the rational embodiment of purposes that Southern extremists had long taught were universal in the North. The crisis helped propagandists falsely identify the whole North with John Brownism. For Harpers Ferry strengthened the hand of extremists and revolutionists in the South as it did in the North, and it likewise discredited and weakened moderates and their influence.

See you next post. If you'd like to get these delivered to your inbox (for free), hit the subscribe button and enter your email address. You may need to check your spam folder for the confirmation email, but I'll never spam you or share your address. You'll just get these posts with the video embedded. (If you use Gmail, you may need to drag the first regular email from your Promotions folder to your inbox, but then you should be good to go.)