Whistler's West Point Experience

During Robert E. Lee's tenure as Superintendent of the United States Military Academy at West Point in the early 1850s, one of his most colorful cadets was none other than James McNeill Whistler.

Fleshing out Whistler's West Point years a bit is a chapter in a 1941 book by William H. Baumer Jr. called Not All Warriors, which profiled academy cadets who achieved fame as something other than warriors:

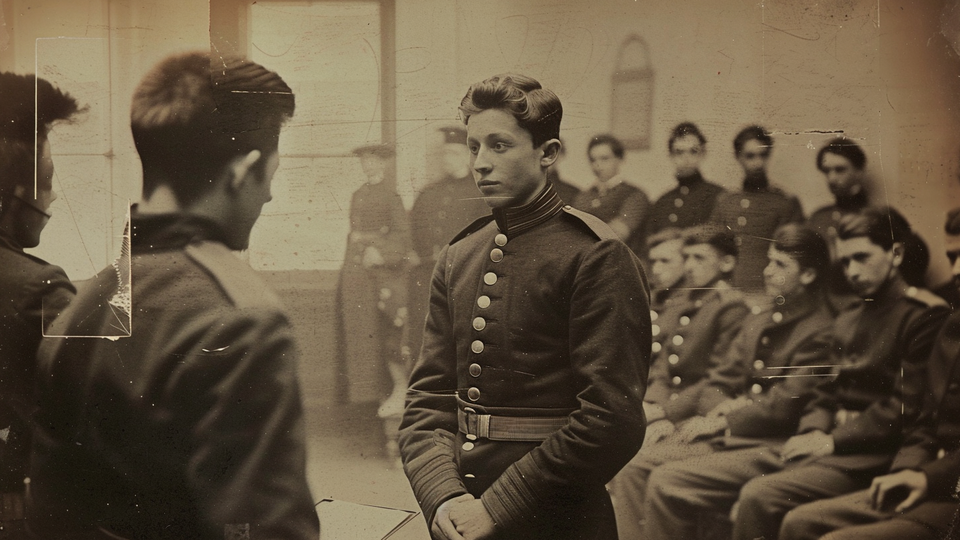

There was more and more the show‑off about James as he grew older. His dark, waving hair with curls, was Byronesque, as was his open shirt front, and the attention-gathering air of indifference as he strode into class. Once there, like many another boy, he bothered not with the lecture being given but busied himself with caricature and portraits of instructors and companions.

At West Point, he continued his dramatic life with its fondness for display, though he lost the long boy curls. The astonishing clothes he later affected may have sprung in contrast from that period of uniformed regularity; and perhaps the rapier tongue also sprang from the curtailment of his natural talkative instincts by the West Point authorities.

The Military Academy at mid‑century was not a home for mollycoddles, and that was what young James Whistler had become. Perhaps the fault was not his own, but rather of a mother who had to lean on her sons when her husband was gone. She wept for his curls; worried over his poor application to academic life; went through agonies that her son might touch a bottle, or fall off a horse when jumping in competition. But that was West Point and American college life of the mid‑century. Her son naturally would lead the parade of pranksters but to believe him a perfect devil among the cadets is to malign them. Below Whistler on the conduct list were a number of cadets, including Francis Vinton, later rector of New York's Trinity Church. The elder Whistler [Whistler's late father George Washington Whistler] too had been caught in various pranks while a cadet.

The curriculum at West Point was mainly one of pure and applied mathematics with only so much of the cultural subjects added as the growing list of graduates demanded. Other than Engineering, Natural and Experimental Philosophy, Chemistry, Algebra, and other technical subjects, the cadets of the 1850's studied English literature and grammar. The Drawing Department had usually gone in strongly for architectural work and for pencil sketching. The professor of Drawing, on a permanent appointment, was Robert Weir, whose own particular liking for water colors caused him to stretch out the course to add 100 hours of advanced work in water colors. Then in the glow of the established artist-turned-teacher, he wasted no time on lectures and verbal inquiry but pitched in with his brush to instruct the cadets by demonstration. The second (junior) class was so dazzled by his skill that few of them, according to their testimony, took away any knowledge of water coloring.

This course in its contrast to the mechanical routine of others in the curriculum made life at West Point bearable for James Whistler. He himself turned to drawing little sidelights of cadet life, particularly one of a cadet on guard — now a treasure in the Academy library. ...

As James Whistler flew swiftly through life, the days at West Point were not wasted. Though he was no shining light in his classes, other than in Drawing, he had no particular difficulty with academic work. He was completing his third year at the Academy when an unfortunate accident to another determined his fate. Professor [Jacob W.] Bailey, head of the Chemistry Department, had a firm conviction that any cadet who was nearing completion of his first three years, and had not displayed any congenital weakness debarring him from a commission should not be hindered in his upward course to a diploma because of a slight lack of chemical knowledge. While on the steamboat Henry Clay on a short trip from West Point, Professor Bailey and his family were caught in the explosion and burning of that boat. The professor's family was wiped out and he was left to care for their burial and to mourn their loss.

Meanwhile, Lieutenant Caleb Huse was in charge. In the small section room with a dozen cadets sitting below and under his nose, the slightest action by any one caught attention. Time and again he would look down at Cadet Whistler's uncombed hair waving its raven dishevelment to the winds. Time and again, Lieutenant Whistler sent Mr. Whistler off to his room to comb the same unsoldierly head of hair. To escape the wrath of his instructor, James Whistler took to combing his hair with his long fingers by running them through it in that gliding way of his. Enough was enough. This man was not cut out to be a soldier and Caleb Huse was not willing to pass over Whistler's slight deficiencies in chemistry.

In fairness to Huse, Whistler did say silicon was a gas.

Whistler spoke fondly of West Point even late in life:

When the well-known American gambler, Richard A. Canfield, had his portrait done by Whistler, the latter noting his suavity dubbed it His Reverence. They laughed and talked together after this ironical quip, and Canfield later observed, "I know that James McNeill Whistler was one of the intensest Americans who ever lived." The gambler continued: "He was not what you would call an enthusiastic man, but when he reverted to the old days at the Military Academy, his enthusiasm was infectious. I think he was really prouder of the years he spent there — three I think they were — than any other years of his life, and he often said to me that the American army officer trained at West Point was the finest specimen of manhood and honor in the world."

See you next post. If you'd like to get these delivered to your inbox (for free), hit the subscribe button and enter your email address. You may need to check your spam folder for the confirmation email, but I'll never spam you or share your address. You'll just get these posts with the video embedded. (If you use Gmail, you may need to drag the first regular email from your Promotions folder to your inbox, but then you should be good to go.)