Montgomery's "Conversational Parliament" Reveals Confederate Divisions Off the Bat

Jefferson Davis was elected Confederate president in 1861 even though said he'd prefer a military assignment. Other Southern figures like Robert Toombs and Robert Barnwell Rhett wanted the job much more than he did, and were in Montgomery, Alabama, when the Provisional Confederate Congress was conducting the election.

William C. Davis's A Government of Our Own: The Making of the Confederacy beautifully grounds the reader in the heady early months of the CSA when its capital was Montgomery, Alabama.

Strictly speaking, when delegates first began arriving, Montgomery wasn't the new nation's capital but the agreed-upon site for a convention. But as Davis writes, there was no time for the strict constructionism that had led states to secede in the first place. It was early February and they had too much to do before Abraham Lincoln took office on March 4. Just how much, however, was a matter of some controversy from the get-go:

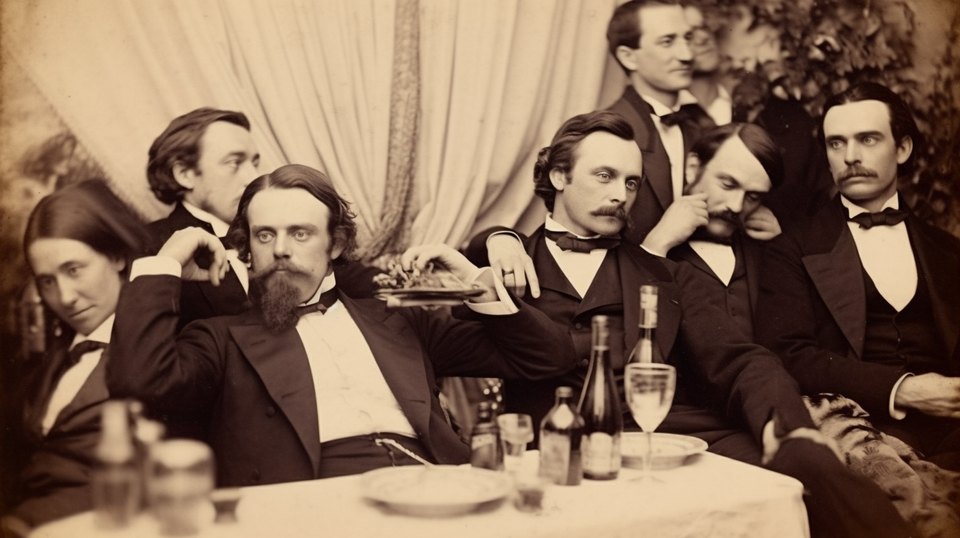

The dining and drinking out of the way, and the spectators kept at a distance, the delegates turned the Exchange [hotel] lobby into a “conversational parliament.” In pairs and groups they traded views, both their own and those of their conventions. Significant differences emerged. Mississippi had already delegated its recent United States congressional delegation to be its representatives in any new Southern government. Consequently [Wiley] Harris and his colleagues believed they should adopt the old United States Constitution as it stood, choose a president, and leave it at that. And Mississippi's choice for president, not surprisingly, was Jefferson Davis. This done, the convention ought to go home and leave the other states to elect their representatives. After all, Harris argued, this meeting was a convention, not a congress.

Louisiana, too, offered some embryonic ideas. [Alexander] De Clouet suggested that they frame immediately a provisional constitution and government on the basis of the old Constitution, select a provisional president and vice president, and then put together a permanent constitution and refer it back to the state conventions for ratification. But he did not say who should form that first provisional government once the constitution was completed. Some argued for immediate elections of provisional representatives, and later ballots for delegates to the permanent congress once the constitution was ratified. De Clouet was a man of wealth, influence, and a good sense. He knew where the powerful intellect in this meeting lay, which is why he and other Louisianians brought with them letters of introduction to [Alexander H.] Stephens.

De Clouet’s proposal came close to the Georgian's own notion of what should be done, but he would go farther. He and the rest of his delegation came armed with the most comprehensive plan of all, endorsed by their convention at Stephens’s behest. They argued for this very convention immediately assuming to itself for up to one year the full legislative powers of a unicameral congress, including the ability to raise taxes, create offices, confirm appointments, frame the provisional and permanent constitutions, and choose a president and vice president. Following state ratification of the permanent document and formal elections of senators and representatives, this provisional congress would then pass out of existence.

[Robert H.] Smith and another of the Alabama delegates endorsed the Georgia plan, and with good cause. They feared putting any question before their people in a referendum. The cooperationist sympathy was too great, and still growing in some counties. The delegates here or coming to Montgomery, even former Unionists like himself, stood committed now to Southern unity. But if getting a government into operation were to be postponed until another election for representatives took place, the possibility of a disruptive number of their opponents being elected loomed very real, and could prove disastrous in any ensuing legislature, perhaps fatal. Stephens, Toombs, and the other Georgians heartily agreed.

It all shocked Rhett and some of his delegation. Every proposition affronted the very principles of independent state rights and determination that impelled them to secession in the first place. “Words are certainly very shadowy in their meaning,” he concluded. South Carolina had one thing in mind when it invited other states to meet with it in convention. Even though they used virtually the same words in accepting, Georgia, Louisiana, and Alabama meant something else entirely. Worse, one of the South Carolinians listening this afternoon suddenly proposed going even further, that the convention assembling here should not itself act as a legislature, but that it should elect the representatives from each of the states to form the permanent congress. Rhett regarded that as “a monstrous commentary upon representation in government.” Thereby, Georgians and Alabamians would be voting upon, and influencing the election of, representatives from South Carolina. As the afternoon wore on, Rhett could see that it was all getting out of hand even before they were started. His defenses went up, his hearty paranoia more alert than ever. There were enemies here, threats to the South, and to himself.

The Charleston convention empowered its delegates to do no more than make alterations to the existing Constitution, submit them to the states for ratification, and then adjourn. Upon ratification, each state convention should then hold elections for senators and congressmen, and also cast ballots for the chief executive offices. The new, lawful congress could assemble before the end of February, count the presidential ballots, and then declare the victors, all without any usurpation of power such as Georgia and the rest proposed.

This convention had no power to elect anyone, Rhett argued. As for the Mississippi plan, if this body did elect a president and vice president, the men would be powerless puppets without a congress. They could not raise money, conduct foreign policy, or even get the executive departments functioning without a senate to advise and consent on appointees. And if the state conventions were to elect senators and representatives anyhow, as Harris proposed, then why should they not ballot for president and vice president at the same time?

Rhett saw the dreaded specter of reconstruction behind this, the fear that if he and others were not careful, they would find themselves reunited with the North under the old Constitution, perhaps with some guarantees covering slavery, but still yoked to their mortal enemies the Yankees. By taking the Constitution as it was, Harris of course spoke for the essential conservatism of all of them. They were not rebelling to erect some radical new shrine founded on principles of their own devising. They were withdrawing from the influence of the corrupt priests of the North who had perverted the existing temple, and they hoped to re-erect it here. Their argument lay not with the Constitution, a document of unparalleled perfection, but with those who interpreted it in ways never intended by the Founding Fathers. Thus Harris and the Mississippians saw no need for altering the existing document. In the hands of responsible Southerners its sanctity would be inviolate.

But Rhett expected that when the Border States withdrew from the Union to join with their equivocal stand on slavery, it would be impossible to put through any amendment limiting statehood to slave states. Moreover, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri were tainted with approbation of high protective tariffs and congressionally funded internal improvements, both issues anathema to South Carolina. Inevitably the Deep South and Border States would have a bitter struggle over those issues. And meanwhile, in theory, the old Constitution would allow the remaining free states of the old Union to join with them, thus effecting virtual reconstruction. “After all, we will have run around a circle, and end up where we started,” Rhett protested.

The fire-eater felt no great regard for the "Georgia project" as he called it. Clearly it represented a usurpation of power, though he felt forced to admit that it was more practical.

In the end, practicality carried the day and they declared themselves a provisional congress. As told (beautifully) by William C. Davis, this story lays the groundwork for two of the book's central themes: how revolutions quickly move to the center for safety in numbers, and how the fire-eaters became marginalized by the process they led the way in setting in motion.

You also get a sense of why the Southern unity that had been sought by John C. Calhoun and others proved so elusive for so long: the Southern states had different interests and divergent conceptions of how state and national sovreignty should interact. The culture wars of the antebellum period weren't just between sections; they were also within them. And the oncoming Civil War would force drastic across-the-board changes in Southern society, as Emory Thomas's brilliant The Confederacy as a Revolutionary Experience shows. He concludes:

The Confederacy was not simply the beginning of the New South. It was a unique experience in and of itself. For four brief years Southerners took charge of their own destiny. In so doing they tested their institutions and sacred cows, found them wanting, and redefined them. In a sense the Confederacy was the crucible of Southernism. And as such it provides a far better source of Southern identity than the never-never world of agrarian paradise in the Old South or the never-quite-new world of the New South. In the context of the Confederate revolutionary experience, when "unreconstructed" Southerners venerate the Confederacy, they are right for the wrong reasons. And when liberated Southerners vilify the Confederacy, they are wrong for the right reasons.

See you next post. If you'd like to get these delivered to your inbox (for free), hit the subscribe button and enter your email address. You may need to check your spam folder for the confirmation email, but I'll never spam you or share your address. You'll just get these posts with the video embedded.