North British Origins of Backcountry Violence

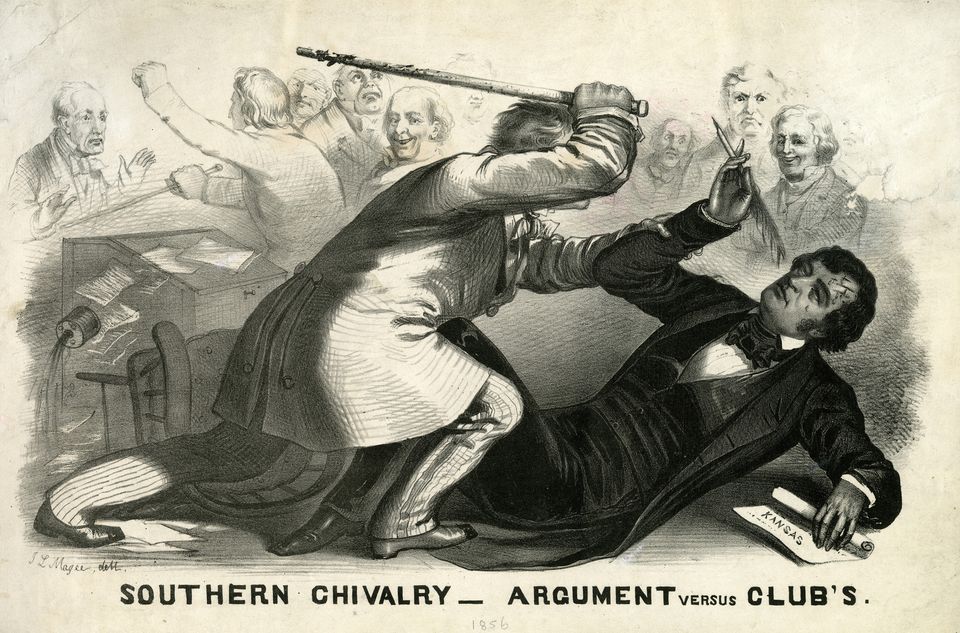

When Representative Preston Brooks of South Carolina beat abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts senseless with his cane, banker and merchant Gazaway Bugg Lamar was one of the few Southerners to express disapproval and warn of the disastrous consequences of the assault for the South.

The reason the hotheaded Brooks needed a cane in the first place was that he had been shot in the hip during an 1840 duel with a fellow South Carolina native, Louis T. Wigall, the future U.S. Senator for Texas. As Eric H. Walther tells it in The Fire-Eaters, Brooks managed to strike Wigfall in the thigh.

As they lay weakened from their wounds, they agreed to allow a board of honor to try again to resolve their conflict.

The board's settlement seemed to favor Wigfall, yet he was not satisfied. I can stand any thing but being told that my honor is as good as Preston Brooks'," Wigfall fumed. ... In March, 1841, Wigfall told Brooks, "I do not consider all matters connected with our late difficulties entirely satisfied, and I shall take the earliest opportunity practicable to vindicate myself." All Edgefield (the South Carolina district where both men resided) believed yet another duel would transpire, "and a feeling akin to horror is inspired by Wigfall's supposed bloodthirstiness." Others interposed again. They agreed to another board's finding, which laid the matter to rest.

Duels remained a part of Southern honor culture even after they'd been banned. The biographies of Jefferson Davis and Alexander H. Stephens are both littered with duel challenges, and the diminutive Stephens was lucky to escape with his life from a fight with Judge Francis Cone in 1848.

Still, as Lamar observed in his letter to Rep. Howell Cobb, Brooks's assault on Sumner went beyond even the norms of dueling. But as David Hackett Fischer writes in Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America, violence had long been endemic to the southern highlands, which had been largely settled by people who "came from territories that bordered the Irish Sea--the north of Ireland, the lowelands of Scotland, and the northern counties of England," where the culture social system – quite distinct from those of the south of England – were shaped by incessant violence, partly because of "[d]ynastic struggles between the monarchs of England and Scotland":

The quarrels of kings became a criminal's opportunity to rob and rape and murder with impunity. On both sides of the border, and especially in the "debatable land" that was claimed by both kingdoms, powerful clans called Taylor, Bell, Graham and Bankhead lived outside the law, and were said to be "Scottish when they will, and English at their pleasure." They made a profession of preying upon their neighbors –"reiving," it was called along the border. Other families specialized in the theft of livestock –"rustling" was its border name. Rustling on a small scale was endemic throughout the region. Large gangs of professional rustlers also "operated on a scale more reminiscent of the traditional American model than any other English equivalent," in the words of an historian.

This violent culture persisted in the American backcountry, including Brooks's neck of the woods, Fischer writes:

An example was Edgefield District, South Carolina, a backcountry area which was known for its extraordinary violence from the eighteenth century to the twentieth. Parson Weems made its violence the subject of a chapbook called The Devil in Petticoats, in which one character exclaims, "What! Old Edgefield again! Another murder in Edgefield ... for sure it must be pandemonium itself, a very district of devils." In 1850, the South Carolina legislature found a "vast number of crimes in Edgefield," and a homicide rate twice the average of the state. After the Civil War, the congressional investigation of the Ku Klux Klan found that Edgefield was "the most violent region in the state." The mayhem continues even to our own time. ...

The world of endemic violence and retributive justice was very similar to the British borderlands, where for many centuries people had been forced to conquer their own peace. Well into the eighteenth century, the borders remained "a region notorious for its continuing lawlessness." As late as 1714, Sir Henry Lidell presented his friend William Cotesworth with a pair of pocket pistols and advised him "never to travel without them." In Cumberland, justices carried arms on the bench, and the public expenditures of the county included daggers for the use of the judges.

This border violence was highly instrumental in its nature, and was often encouraged by local elites. In 1712, for example, the board of directors of a powerful coal cartel in the North of England, "including gentlemen and citizens of the highest repute," openly extorted their tenants to "cut-up" a "wagon-way" that belonged to a rival group.

Here was yet another continuity which extended from the border country of North Britain to the backcountry in the eighteenth century, and to the southern highlands in our own time.

Seen in this light, Brooks, who died aged 37 in January 1857, shortly after returning to Congress, was continuing a tradition that originated not in the South itself but the North British borderlands.

See you next post. If you'd like to get these delivered to your inbox (for free), hit the subscribe button and enter your email address. You may need to check your spam folder for the confirmation email, but I'll never spam you or share your address. You'll just get these posts with the video embedded.